There is more and more evidence, given wage growth and other indicators, that an inflationary uptick of some kind is afoot. Before analyzing its ramifications, or worrying about a $25 loaf of bread, looking at the past can help us understand how this might play out.

The last significant inflation surge that the US and the developed world experienced ended way back in 1981. Which means, of course, as is so often the case with investment cycles, that there is hardly anyone around now managing money who was managing portfolios during the years of high inflation, 1969-1981. What’s more, the family office model had yet to be established.

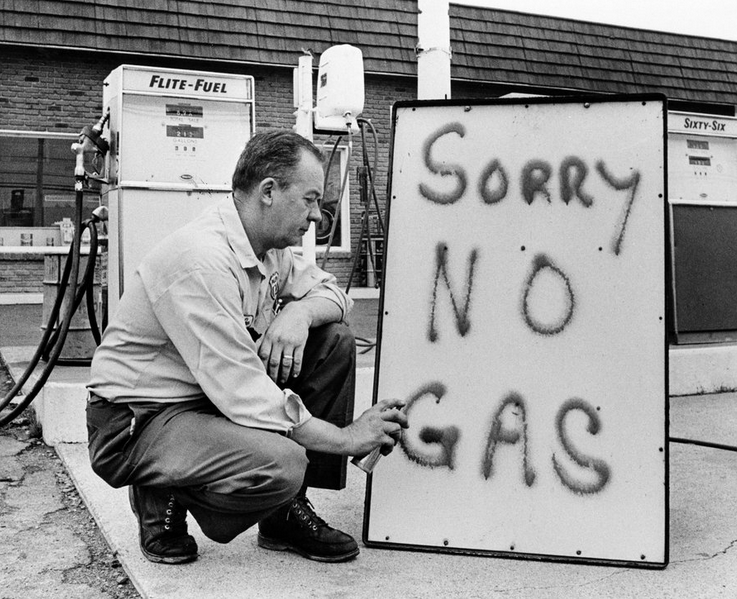

It is hard to describe the kinds of things that happened in those years; they were so unlike the years since. I was not old enough to be managing money then, but I do remember the Nixon administration putting actual price controls into effect on goods and services (and salaries). As one might imagine, it was a total failure, not to mention brutally unfair to working men and women who had their pay frozen while having to deal with gasoline, heating fuel and other external price shocks. These price swings were real. The Arab oil embargo that began in 1973, for example, spiked massive prices in fuel and rationing of gas, with people forced to wait in long lines to fill their cars up.

Concurrently, interest rates hit all-time highs, with bond yields and borrowing rates generally in a steady climb during the entire period. Thirty-year US Treasury bonds peaked at a 15.25% yield in the fall of 1981, and in February of 1982 the highest auction rate ever for a sale of US Treasuries was reached: a 14.56% average yield.

During these times, the financial press was filled with dire warnings from prognosticators telling investors to beware. Of course, investors buying and holding those bonds for the next 30 years never looked back. It was the greatest “clipping coupons” investment of all time: being paid 14.56% for bonds bearing the full faith and credit of the United States government, a.k.a. the risk-free rate. And if you passed on the bond auction and bought equities instead, you did just fine also, as 1982 marked the beginning of the greatest long-term bull market to date in both bonds and equities.

Those high interest rates at the end were to a large extent the work of Paul Volcker, the monetarist Fed chairman who forced Fed funds rates aggressively higher until the back of inflation was broken.

So, what can family offices and other investors learn from what happened in those aberrational years? History offers a few clues. First, the decision to buy risk-free government bonds was in fact a difficult one. Although in hindsight it seems obvious to buy yields of 15% locked in for 30 years, up until rates reached that level, everyone who had bought bonds from 1969 to that point had lost money. The term coined for bonds during that period was “certificates of confiscation.”

The winners during those years were commodities and commodity producers, especially energy companies. Residential real estate had several continuous mini-booms across the country, despite rising mortgage rates. I recall my parents buying a house for $17,000 in 1971 and selling it five years later for $44,000, with no one thinking that such a return was all that impressive. One of the lesser-explained reasons that so many people who retired in those years accumulated wealth well into their retirement is that they sold the family homes they had lived in for 40 years (with the mortgage long paid off) at prices higher than they ever imagined, then plowed the money into bonds and stocks at the very beginning of the great bull markets for each.

Value stocks that generated cash and paid dividends did well (the ’70s were the decade that Warren Buffet made his greatest buys), and it was a stellar environment for stock pickers. George Soros and his partner Jimmy Rogers made insane returns in those years long and short, and the legend of Peter Lynch and the magnificent Fidelity Magellan Fund was established.

The greatest losers of the era were U.S. presidents. We all know what happened to Nixon; Gerald Ford could not get the economy or inflation to cooperate (one of his ideas was to make buttons that said “WIN” for Whip Inflation Now), and he refused to offer a bail-out to New York City when it teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, inspiring the famous Daily Newsheadline “Ford to City: Drop Dead.” Jimmy Carter went on national TV wearing a cardigan sweater and urging Americans to save money by turning their home thermostats way down. (Americans didn’t really take to the concept of their president lecturing them on alternative methods of keeping warm, or about how to “learn to live thriftily,” Carter’s exact words.)

The overall investing lesson of the period was that it was a great time to buy productive assets or businesses with true prospects, but that one had to be patient and suffer some price dislocations while waiting for the full payoff.

There are key differences now. Inflation and its components are better measured and understood; global production methods source lower cost alternatives more efficiently; debt is far more pervasive (not many people have mortgage-free homes today and those at retirement age are generally short savings); and the Fed very carefully telegraphs its intentions ahead of time so that the expectations of further tightening may substitute for the real thing.

It was close to 40 years ago, but there are some salient and didactic points worth noting from the last inflation cycle. Perhaps increasing the focus on productive assets is a worthy tack.